First, a 2022 Merlot from Central Washington. Then, a Pilsner Urquell, followed by a Guinness stout, a No-Li amber ale, a Sierra Nevada pale ale, two nonalcoholic beers and a Trader Joe’s tequila.

Three tasting glasses are perfectly lined up behind each beverage: one for brewer Thomas Croskrey, one for entrepreneur Cal Larson, and one for me.

Here at Townshend Cellar in Spokane, Larson is introducing me to a unique product that has the potential to disrupt barrel aging for wines, beers and spirits — a process that has remained essentially the same since the Celts used wood barrels to store wine before the Common Era.

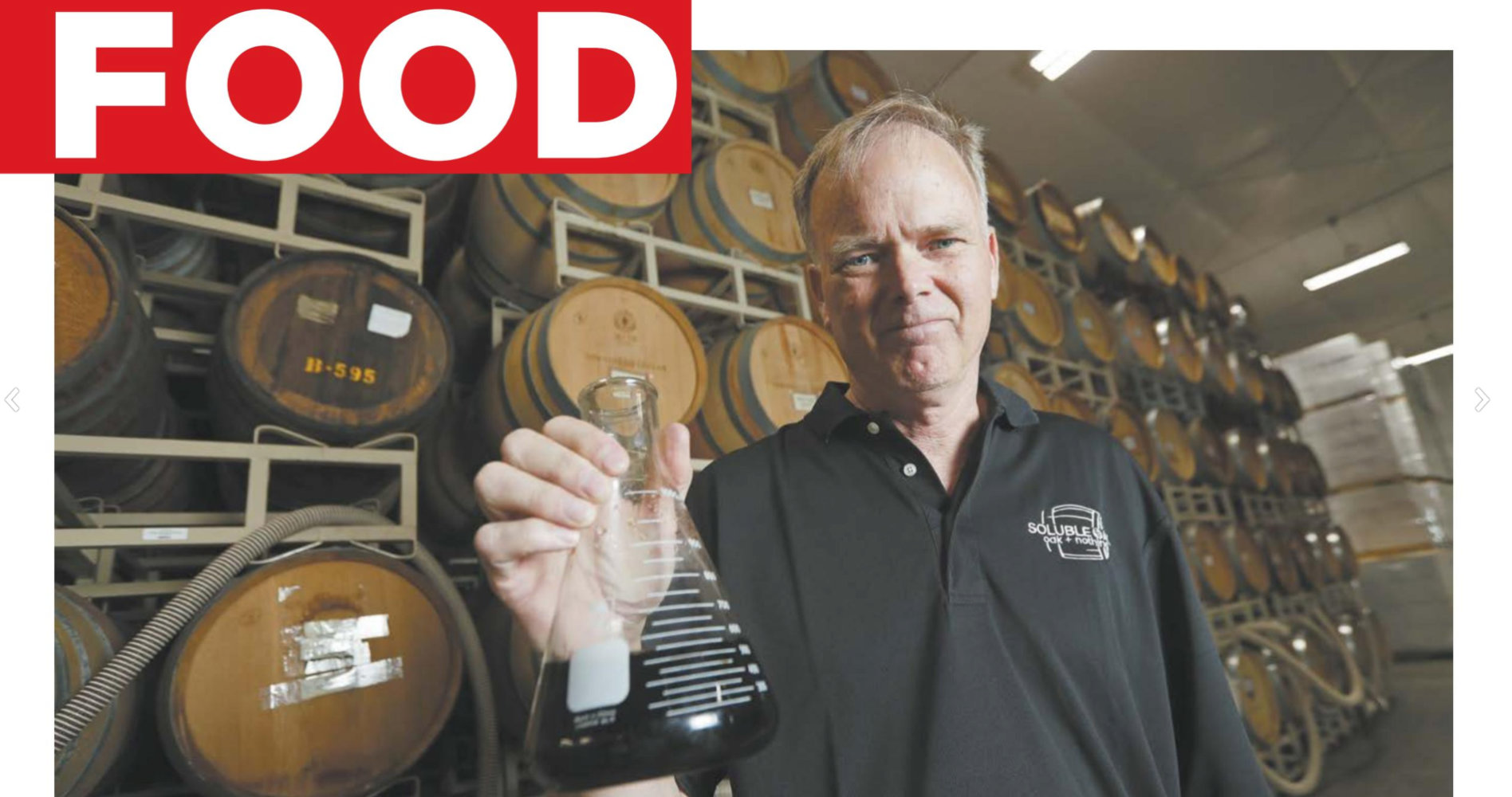

Larson is the founder of Soluble Oak, a local company that has figured out an all-natural process to extract flavor compounds in white oak wood and condense them in a liquid form without additives. A few drops of Soluble Oak can instantaneously make wine, beer or liquor taste like it’s been barrel aged for years.

It’s a bold claim, indeed — hence the taste test that he’s set up for us in the front of the winery.

“I feel like the industry is a little bit like coffee was in the ’80s,” Larson says. “There’s a few companies that really understand the nuances of oak and the problem with barrels. The problem is wine, beer and spirits are not extracting the right thing.”

Croskrey of Emrys Fermentations is here, too, because he and Brendon Townshend have been instrumental in fine-tuning the product. Other local producers like The Grain Shed, Hat Trick Brewing and Dry Fly Distilling have also tested it. Chances are good that local imbibers have gotten to sample a pint or glass that benefited from Soluble Oak.

But now, Larson, an international salesman by trade, is ready to take the innovation global. If it takes off, Spokane would be the birthplace of one of the only significant changes to barrel aging since Romans stole the idea from the Celts.

White oak is one of the most common trees in North America, covering the eastern half of the U.S. from Maine to Minnesota to Texas and Florida. It grows best in cooler northern climates, including much of Europe. Some of the most sought after old-growth wood comes from France.

Before he was an inventor, Larson was a lumber salesman who specialized in selling American white oak to Western Europe. It’s a “bizarre niche” that hyper-familiarized him with the molecular differences between white oak grown in different areas. In France, for instance, buyers and sellers distinguish trees by which specific French forest they grew in.

White oaks can live for hundreds of years, which is why France is currently chopping down trees planted in Napoleonic times. Many of those trees are destined for barrel making, since almost all wine barrels are made from white oak.

But in order to be made into a barrel, the wood has to be clear of all knots. Larson says that’s typically only the bottom 12 feet or so of the tree, (the average white oak is between 80 and 100 feet tall), and only the outer third of that section of the trunk. Which is a shame, Larson says, because barrel makers end up missing out on a lot.

“It’s sort of like a watermelon — the best flavors are in the middle,” he says. “But the problem is, in the middle, there’s a bunch of knots. So the industry as a whole is not is not extracting the best flavors.”

Then, to become a barrel, the wood must go through heat and water treatments that kill many of the 200 or more sensitive compounds in white oak, Larson says.

Once the barrel is finally finished and filled, the alcohol inside slowly extracts the remaining chemicals, like cinnamonols and vanilloids that add those desirable cinnamon and vanilla flavors. It also slowly oxidizes, which helps round out a young wine if the process is minimal and slow enough.

White oak is prized because the hardwood doesn’t allow for too much oxidation or evaporation. But the density also means the alcohol can only penetrate 5 millimeters or less into the side of the barrel, leaving any of the flavor compounds in the remaining 80% of the wood untouched and unutilized.

As Larson sold more and more wood, he got more and more bothered by all the waste in traditional barrel aging. So he recruited two chemists to figure out how to extract flavor from all parts of the tree.

After seven years of experimenting, the team invented a secret, patented process that creates a liquid form of the wood without any synthetic additives. They also offer three different “roasts” that highlight different flavors within white oak. Plus, they separate American oak and French oak products so that manufacturers can choose which flavor profile they prefer.

“At the heart, it’s an environmental company,” Larson says. “The goal is to point the industry towards, like, don’t do this crazy stuff that takes down old-growth forest. There’s a much better way to do it that doesn’t involve environmental devastation.”

Not to mention that Soluble Oak’s final product costs about one-third as much as a comparable amount of barrels. Talk about saving green in multiple ways.

The tasting test at Townshend starts with the red wine first. After an introductory sniff and sip, Larson drops one drop of Soluble Oak into each glass. I’m skeptical, because I don’t have a very advanced palate and it’s a pretty tiny drop.

But without Larson or Croskrey saying anything, I feel a difference in the next sip immediately. Yes, feel — the wine feels softer in the mouth and the aftertaste is rounder. Larson adds one more drop and that’s when more prominent wood notes appear.

“There’s a lot of oak products on the market, but they taste like syrup or medicine,” Croskrey says.

He was ready to send Larson away when they first met because he was so skeptical that any liquid product could taste good. Now, he’s changed his mind.

Soluble Oak doesn’t taste artificial “because it’s impossible,” Larson says. “We don’t use anything artificial.”

With just a drop, the pilsner becomes softer and deeper. The Guinness gets more chocolatey. The pale ale suddenly has vanilla notes, the NA beers are more complex and the tequila loses an unfriendly edge. It feels like magic or witchcraft. But it’s just chemistry.

Larson has lofty goals for his sapling start-up.

“Since it’s a small operation, our goal is to get a couple big fish on the line, and then build up manufacturing, sales staff, etcetera,” he says.

This isn’t something that will be available anytime soon for the public to do their own taste test like ours. But it could mean your favorite wine, beer or liquor that usually has to wait a few years in a barrel could be hitting the shelves much quicker.

“I’m just stoked to see this sort of a product that’s actually good, and that does live up to the sustainability claims,” Croskrey says. “It’s tasty. It’s responsible. I’m proud to know him.”

PROPRIETARY TECHNOLOGY AND MANUFACTURING – SOLUBLE OAK™️ IS AN ENVIRONMENTALLY CERTIFIED SOCIAL PURPOSE CORPORATION PROMOTING SUSTAINABLE OAK. FDA APPROVED.

New Release of innovative product for wine combining the Best of French (mouthfeel) with the Best of American (flavor).